Time and use all too often cause modern buildings to wear in a negative and destructive way. Present-day construction does not tend to allow for patina, or wear, relying instead on the ability to replace standardised parts, rather than on repair as a means of building preservation and enhancement. The modern preference for replacement over repair, militates against the narrative, sentiment and soul that emanates from buildings of an older construction.

Design and construction are too often regarded as separate elements, when actually they are intrinsically linked and inter-dependant. An appreciation of how much they depend on each other is fundamental to the ethos and operation of our own design and build studio. The emphasis here is on the act and art of construction being essential components of design education. This is summarised well in the Studio brief which reads: “we do not educate builders; but architects who can think constructionally and work critically.”

I have looked a lot at rural and vernacular buildings for inspiration on how to build, as typically they utilise materials that you can find directly from around you in the landscape. This sort of approach to construction encourages you to adapt to and make the most of the resources immediately available to you, particularly when same may be scarce and so alternative resources need to be considered for use. This emphasis on the ecology of building is particularly important when striving for sustainability in building practice, rather than simply paying lip-service to it. Materials that exist and can be sourced from the landscape that surrounds any given site, have a natural resilience to the environmental conditions of the area. In addition, little movement takes place in the logistics involved in the gathering and processing of such materials. These considerations are almost entirely disregarded in contemporary architectural practice, in which materials are sourced through highly energy intensive extraction procedures and are then transported considerable distances to and from processing plants to their end destinations, with a significant carbon footprint the inevitable consequence.

As a means of challenging the contemporary practice of the architect and the buildings that seem to rise, like a phoenix, from the ashes of a torched public-use electric scooter, I have designed and built this goat house at Hjerl Hede. This has been as an extension and enthusiastic endorsement of Studio 2D's previous work to date there. I have had conversations with a variety of people who have positively influenced my study of architecture, so to gain a greater insight and understanding of the approach to building in the present-day, specifically around striving for more sustainability in the practice of architecture and construction. The people I have spoken to have all had backgrounds in a variety of different methodologies of both art and architectural practice, but all share a common interest in construction. Undocumented conversations were also a significant part of the development of the project on a daily basis and with all manner of people that I engaged with. These dialogues and the important discussions that I recalled having had with others, were matters that I wanted to document in a more permanent manner in the manifestation of the goat house in its finished state.

The goat house is an addition to the already existing built structures at Hjerl Hede. In designing and constructing the goat house I have tried to expand upon certain aspects of the existing structures and in doing so produce an example of a building that operates on the basis of the model of necessity, something we see less and less of in present day life and construction.

The goat house sits within the museum boundary. This means that extra sensitivity has needed to be applied to the design of the building, with inspiration taken from the principles followed in the construction of adjacent buildings, only not in a way that renders it a museum building. I am particularly inspired by the vernacular structures of Northern Europe. Many have been constructed from materials sourced from the immediately accessible natural environment, with all the benefits that go with being able to gather, transport and process materials sustainably.

The goat house does not attempt to be an historic building, nor does the process by which it was built attempt to be a re-enactment of historic building practice. It is simply influenced by existing vernacular structures and the techniques used to implement them. It is a contemporary building and the process of its construction has utilised both historic and contemporary techniques, though with a less is more approach and with solid simplicity at their heart. I repeatedly asked myself during the process "is this necessary" and "is this logical"? Questions that I fear are often passed over in the grand schemes of present-day architecture.

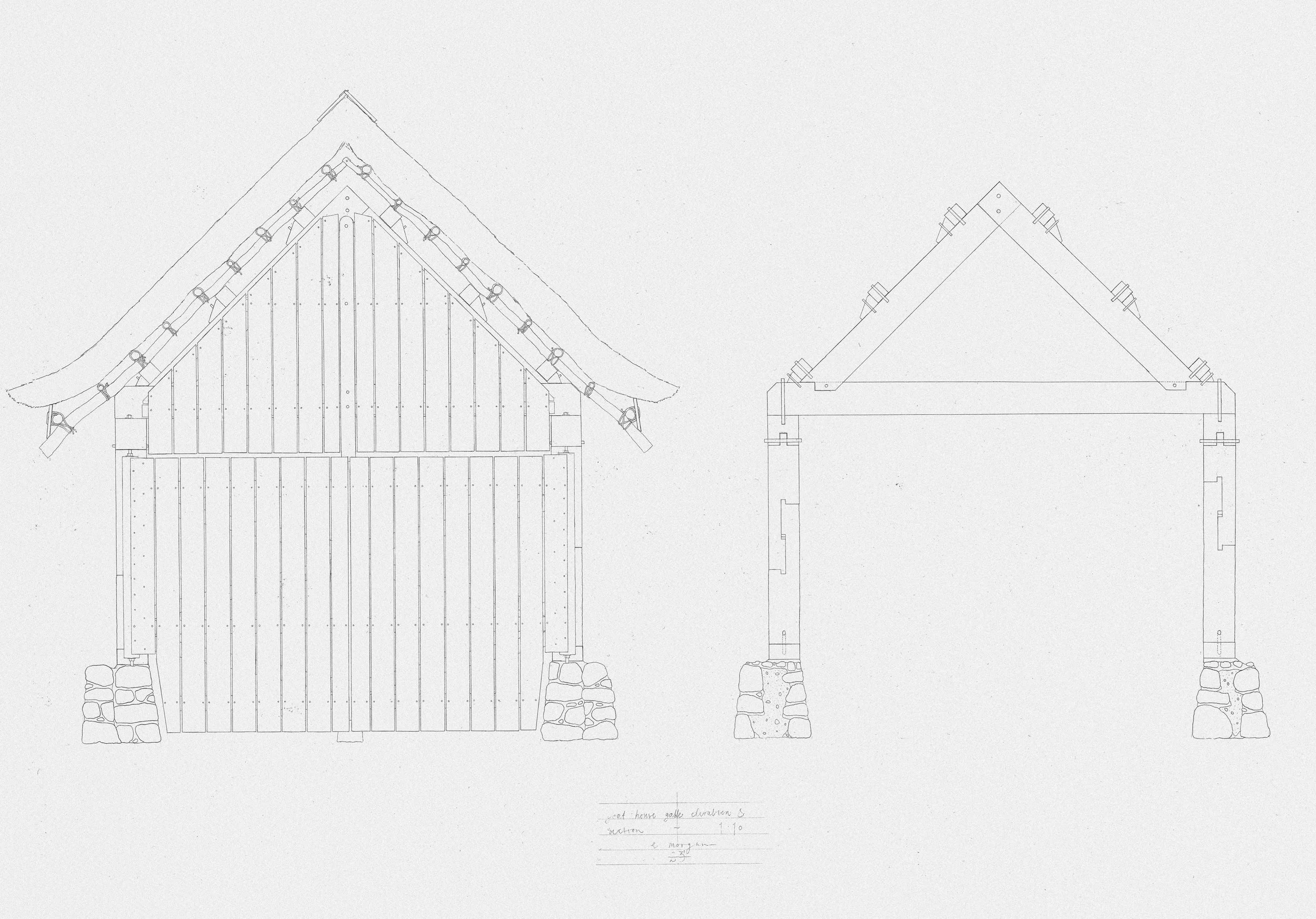

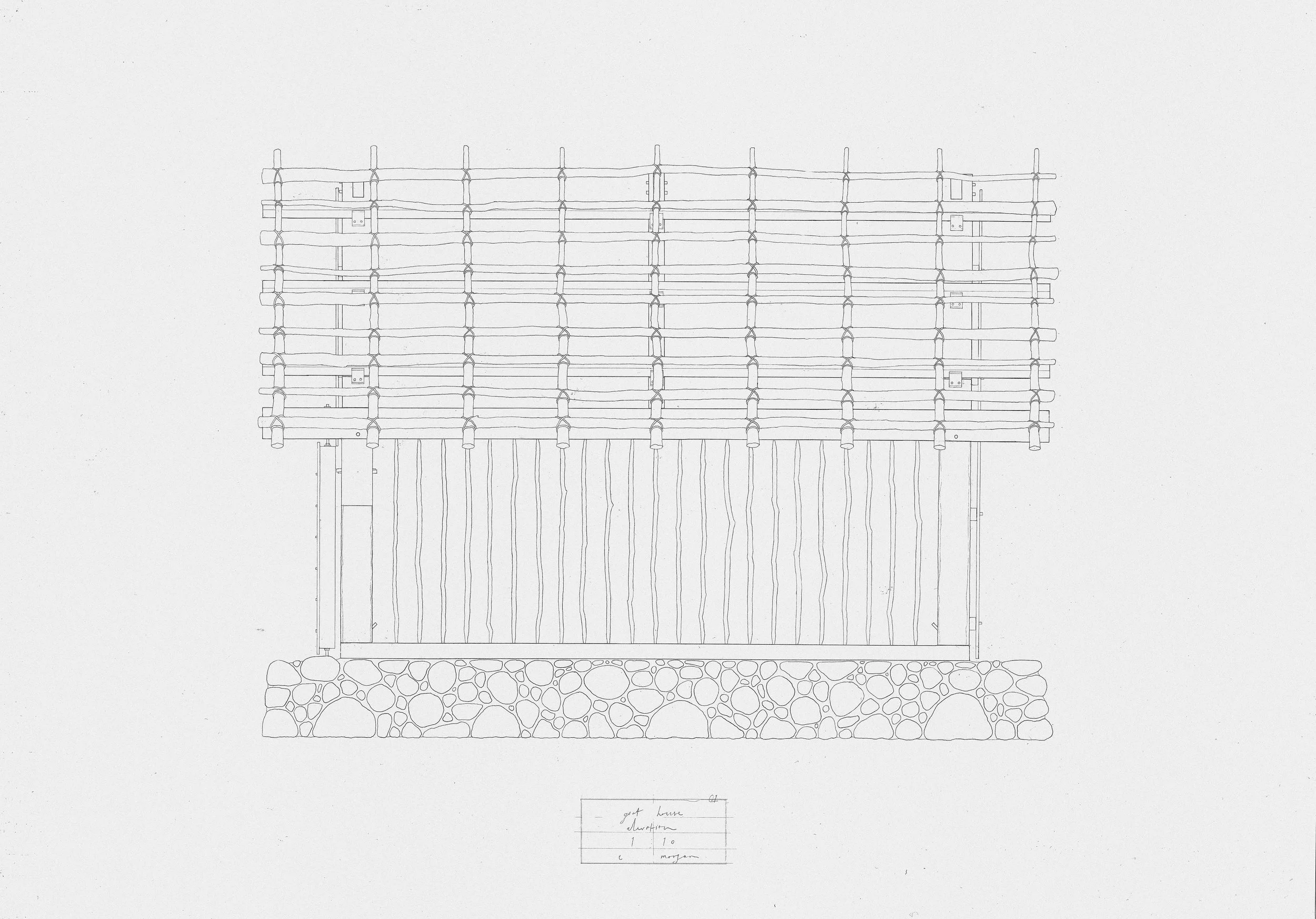

In terms of the structure of the goat house, a minimally disruptive excavation of the topsoil to produce a level surface was followed by the construction of a low granite wall was built up from fieldstones collected from the premises of the museum for the foundations/base of the structure. Larch felled in the area and processed from a local sawmill 20 kilometres away form the main timber frame structure of the goat house and the roof build up and studs for the walls are constructed from young spruce trees sourced from the forests that surround Hjerl Hede and which I felled and processed myself. The approximate footprint of the goat house is 17.5 square metres with a length of 5 metres and width of 3 metres, standing at 4.2 metres at the peak of the roof. These dimensions have been adjusted to meet the requirements for what the goats need, as advised by Carsten, the livestock keeper at Hjerl Hede.

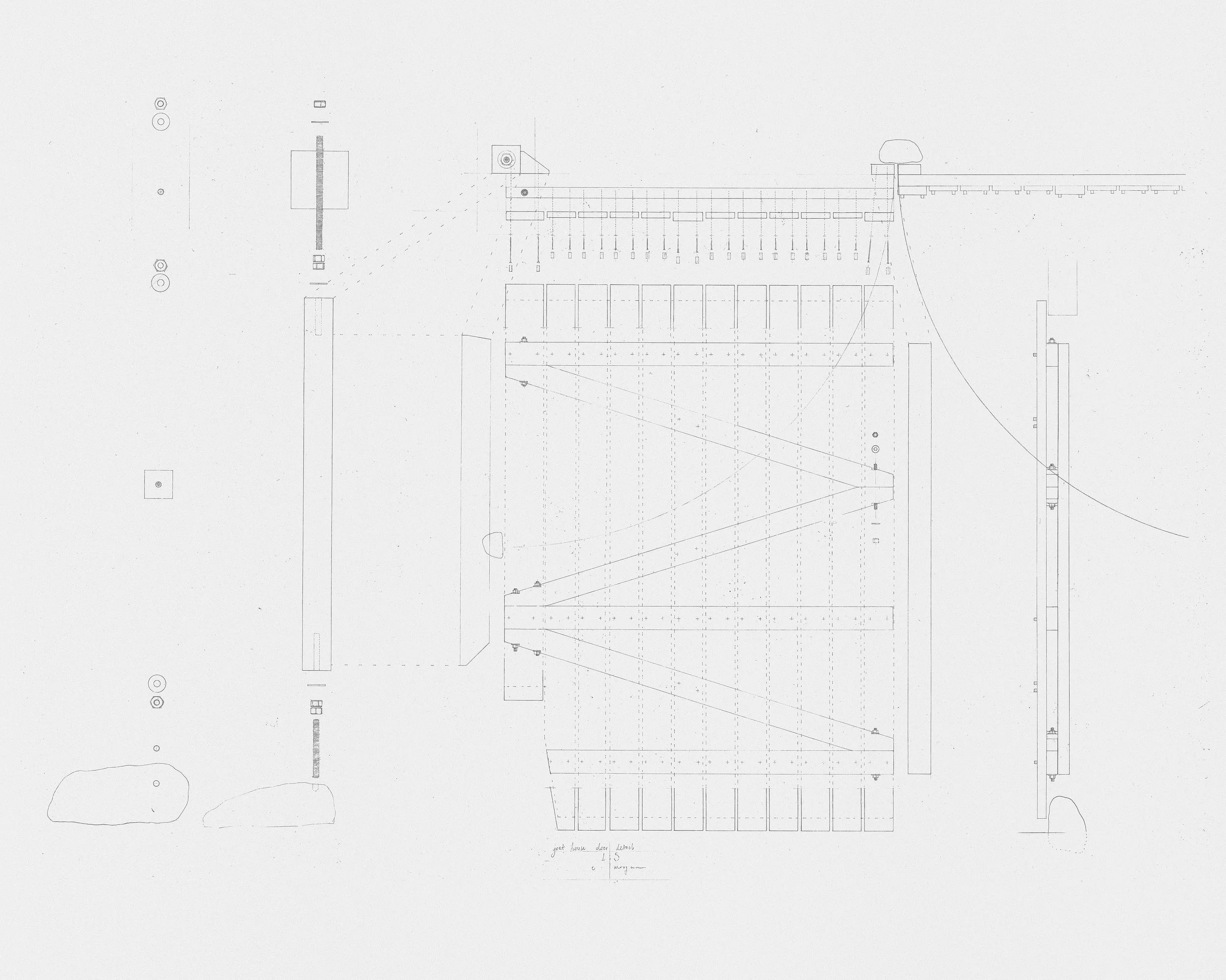

The design processes that I have followed are somewhat detached from the usual ones that apply in architecture. Design and construction processes have been merged. Initial drawings were made to detail aspects of the structure based on the assumption that the materials specified were going to be available. These were adapted, however, as variations became necessary, or complications with the methodology of the construction arose. Such an approach was to achieve a construction process that was directed as much by necessity as it was by preference. By way of example, the necessity of the approach to the construction of the goat house came from making do with and utilising resources and materials that were immediately available, the existence of which resources and materials, at the beginning of the process, were unknown to me. I have highlighted the occasions on which the construction process had to be adapted, as they arose, on copies of the drawings I took to site with me.

The goat house project was conceived as part of my 9th semester project and commenced when I collected and repaired four timber frame posts that I found at Hjerl Hede whilst carrying out studio work there. I made some quick surveys of each post that day, noting defects and characteristics etc. I then cut them to 2.8 metres, the length of the back of the van, so that we could drive them back to Aarhus.

Upon my return to the city I continued the survey work with one of the posts in more detail, photographing each side of it and making a 1:10 scaled hand drawing of the sides and their imperfections.

I then began the mending process, analysing which parts of the post were unusable. In two of the four cases, the tenon at the top was completely rotten and needed replacing as well as the sides where it had been dowelled and rot had found a way in. Following the mending, I went over the original drawing showing the implementation of the new parts.

After a conversation with Hjerl Hede and Carsten the livestock keeper, I was given the opportunity to build a small goat barn in one of the lower fields of the farm for my thesis project, utilising the mended timbers to form part of the structure of it. These four posts were reappropriated in the structure of the goat house, one in each corner.

To document the project development that took place, I made a film of the process, with a focus on materials and their origins as well as the processes and techniques that were used to implement them in the subject structure. The inspiration for the project and the construction of the goat house came from buildings and people who have inspired me, with theoretical interjections influencing the construction process in a critical manner at various points. In the film documenting the construction of the goat house, I have tried to create layers of narrative, from on-site present explanations of how and why the goat shed is being constructed in the way that it is and with important junctures where significant decisions and references were made. In this way I hoped to be able effectively to present the project as an endorsement of how effective the design and build approach to the construction process is.

As part of my project I also prepared a series of 1:10 scale drawings, including sections, plans and elevations, I will also present a model from my previous semesters work, as well as a the film documenting the build process.

As can be witnessed in the short film I have made, at various stages during the construction of the goat house I collaborated with and received assistance from friends, who offered their help in exchange for some experience and understanding of what I was doing. In addition, I was consulted at points during the process about aspects of it that they had some particular interest in. I have to acknowledge that these encounters proved to be some of the most fulfilling and influential aspects of the project. Most of the people who attended knew something about that particular part of the process and/or learnt something by doing it, or conversing with me about it, as I did in the same way from and with them. The historic tradition of knowledge about and application of building methods being transferred by word of mouth, is a dying aspect of building culture, but still an important one and also something that has conferred on virtually every built environment its cultural identity. My experience of sharing knowledge with others during the course of the goat house project gave me an insight of just how valuable the transfer of knowledge in such a way, can be.

I would particularly like to highlight the importance of process in this project. The goats required a dwelling that met their basic needs, something that was explained to me by Carsten at the outset. My role, therefore, was to provide a structure that met those basic needs. I was keen, however, to do so in a way that was sympathetic to the environment in which the structure was to be located, whilst simultaneously using the design and build process as an opportunity of paying respect to historic building cultures and construction techniques and using the project as a means of showcasing same to others. The museal context at Hjerl Hede was a perfect environment to do this, surrounded by buildings that trod lightly on the land and enabling the use of regionally sourced materials and building techniques that have adapted to suit their environments through generations of craft development and oral tradition. By filming the project and documenting the construction process, I hope to have been able to draw the attention of others to the variety of elements that have been the inspiration for and played and integral part in that process, in the hope that those that have been touched by the project, may wish to replicate aspects of same themselves. In so doing I sincerely hope also to have played a small part in preserving those elements for posterity.

As previously touched upon, architecture of the contemporary era, often fails, in my view, to acknowledge the passage of time. As Juhani Pallasmaa notes:

“The inevitable processes of aging, weathering and wear are not usually considered as conscious and positive elements in design, as the architectural artefact is understood to exist in a timeless space, an idealised and artificial condition separated from the experiential reality of time.” Juhani Pallasmaa

Little account is taken of the fact that materials are in a constant state of change and how they are now, is not how they will be in the future, or ultimately when they cease to exist at all. For that reason, striving for something that is perfect and permanent in construction terms is futile. We are unlikely to be around to experience the demise of the buildings that we design and construct, but their inevitable demise significantly impacts those who utilise the buildings. This makes it all the more important that the way in which they are designed and constructed, is with their long term preservation in mind, an intrinsic consideration of which should be around the manner and method of their construction and most importantly the materials that are used for that purpose.

John Ruskin believed that, “Imperfection is in some way essential to all that we know of life. It is the sign of life in a mortal body, that is to say, of a state of process and change. Nothing that lives is, or can be, rigidly perfect; part of it is decaying, part nascent... And in all things that live there are certain irregularities and deficiencies, which are not only signs of life but sources of beauty.”

Alvar Aalto evolved Ruskin's idea further. He referred to the issue as "the human error" and condemned the search for an objective ideal of perfection: “One might say that the human error has always been part of architecture. In a deeper sense, it has even been indispensable to making it possible for buildings to fully express the richness and positive values of life.”

The Roman architect Vitruvius maintained the idea that the architect must be skilled in both "fabrica" (craft) and "ratiocinatio" (reason) an idea that resonates with me and one that I have attempted to put into practice. The modern day architect is far removed from building practice. I believe that tactility and an understanding of the nature of materials should be a compulsory part of architectural education. Without this, the architect cannot have a complete appreciation of the feasibility of his designs or the integrity of the structure to be created thereby. As a consequence, architecture can start to become deficient in its cultural identity and ecology. "Never has so much construction been based on so few ideas." Adam Caruso

First and foremost, I am an architect and not a builder, though I genuinely believe that a fully informed appreciation of the former, is best gained by some engagement with the latter. Jane Rendell argues that working between disciplines demands that: "We exchange what we know for what we do not know, and that we give up the safety of competence and specialism for the fears of inability and failure, the experience of interdisciplinary work produces a potentially destabilising engagement with existing power structures, allowing the emergence of fragile forms of untested knowledge and uncertain understanding." Jane Rendell. The creation of the goat house was the result of an application of the two disciplines of architecture and building. Having made drawings of how I expected the goat house to be constructed and what I imagined the finished structure would look like, those drawings were necessarily amended as the project evolved and as I gained more knowledge and understanding of the building process, which previously and in material respects had been both untested and uncertain.

To conclude, there are, of course, fundamental differences between the processes involved in building a goat house and those required for the construction of residential or commercial structures in the contemporary built environment. That is not to say, however, that the aspirations of the design and construction principles utilised in the building of a structure as simple as a goat house, in particular around the approach adopted to the sourcing and choice of materials and the manner of their utilisation, are any less valid, or that aspects of same cannot be transferred to the design and construction process applied to more grandiose domestic building projects, particularly in a rural context. If the sort of methodology I have referenced in this project for the construction of a structure as simple as a goat house, can be used in just a tiny way to challenge modern architectural ideals and construction practices with their emphasis of permanence over maintenance and in so doing endorse a revival of traditional ideals and practices, then that, in my view, has to be a good thing.